On the morning of February 20, 1909, Parisians who opened their copy of Le Figaro with their café et croissant and might have been amused, outraged, dismayed, enlivened, non plussed, or simply puzzled by the “Manifeste de Futurisme” by one Filippo Tommaso Marinetti that appeared on the newspaper’s front page.

In an era that can rightly be called the Age of Manifestos or the Age of Isms, the Manifesto of Futurism harks back to Marx and Engels and sets the tone and style for those “isms” to come, including Vorticism, Dadaism, and Surrealism.

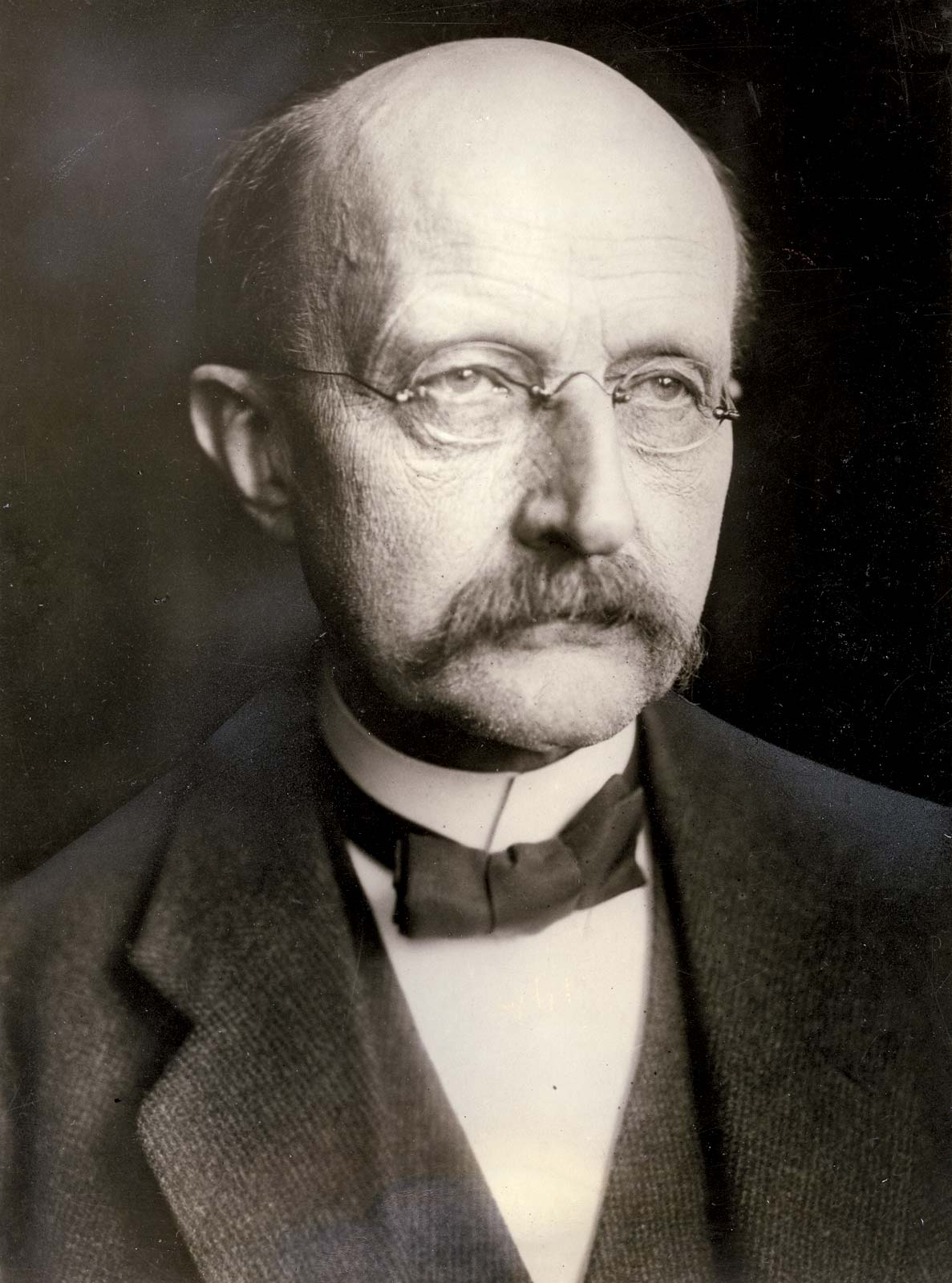

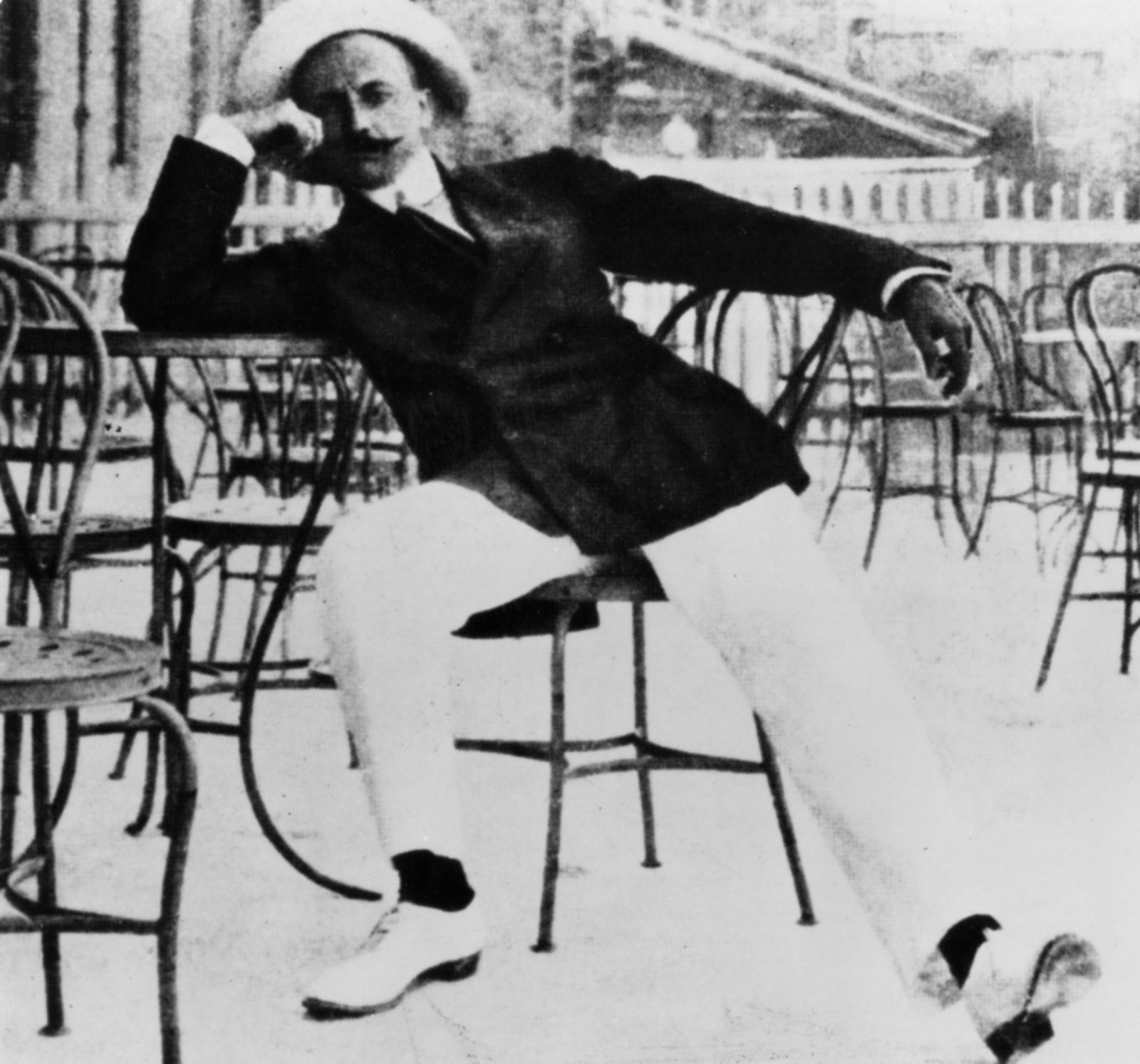

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in a 1915 photograph; britannica.com

Marinetti’s manifesto was, to put it mildly, over the top.

The manifesto is one part prose-poem, one part wholehearted embrace of modernity, and one part a hysterical screed decrying anything perceived as peaceful, bourgeois, traditional, or feminine.

To read more, click here.